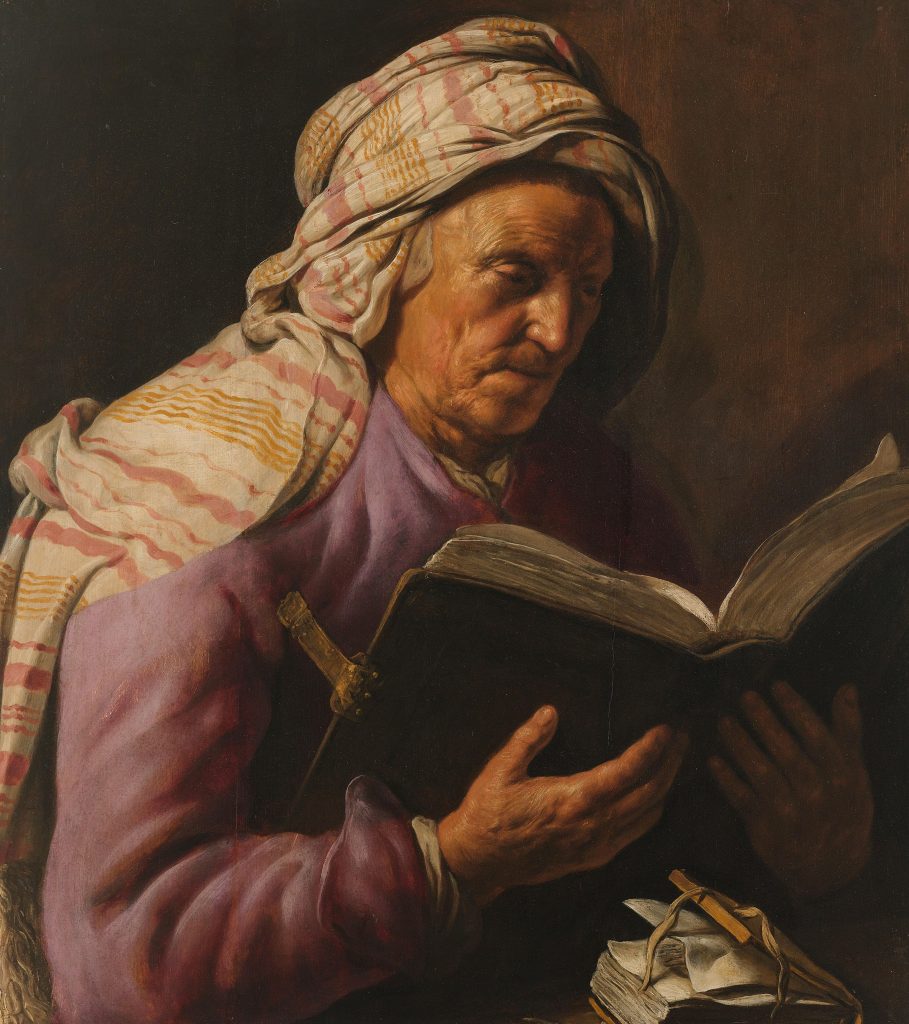

Master I.S. Portrait of an Old Woman with a turbain-like Headdress, 1651, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Masterful Mystery: a possible solution for the enigma of the Master I.S.?

Kunsthistoricus Benjamin Binstock vroeg Museumkijker plaats voor een essay onder bijgaande kop. Daarin oppert hij een mogelijke oplossing voor het raadsel van de Meester I.S. Wie schuilde er achter de initialen van deze grote 17de-eeuwse kunstenaar, tijdgenoot van Rembrandt, Jan Lievens en Gerrit Dou? In Museum De Lakenhal is tot en met 8 maart een tentoonstelling aan de Meester I.S. gewijd, georganiseerd met de Serlachius Museums in Finland in samenwerking met de Radboud Universiteit en Museum Rembrandthuis. Vanwege de sterke stilistische overeenkomsten is het volgens De Lakenhal aannemelijk dat de Meester I.S. in aanraking is geweest met kunstenaars uit Leiden. Benjamin Binstock gaf colleges kunstgeschiedenis in New York en schreef onder meer een spraakmakend boek over de toeschrijving van werken van Vermeer. Hij woont sinds 2018 met zijn familie in Nederland. Museumkijker is Nederlandstalig maar maakt graag deze aanlokkelijk geschreven Engelstalige uitzondering.

Benjamin Binstock

“Masterful Mystery,” at the Leiden Lakenhal, is an exhilarating exhibition that you have to see! We do not know the name, the place of origin, or even the gender—the visual evidence provides grounds for confusion on the last point—of the artist known as “The Master [or Monogrammist] I. S.” for their signature initials, mostly on top of one another (in ligature). The exhibition is the brain-child of Tomi Moisio of the Serlachius Foundation in Mänttä, Finland, and the Lakenhal curator Janneke van Asperen, who pithily proposes in her engrossing catalogue essay that the situation “leaves us no choice but to focus on the work itself as the only key to unlocking the mystery”; you literally have to see this show.

An unknown artist would not by themselves necessarily merit such attention, yet Master I. S. displays the highest technical achievement and originality, in a diverse and deeply satisfying group of paintings, some of them newly discovered for this exhibition: a masterful mystery tour. Beyond the catalogue’s title “Rembrandt’s contemporary,” the artist knew and learned from paintings by young Rembrandt and was perhaps among his greatest followers. At least that potentially controversial thesis will be put forward in this review, along with a possible solution for the enigma of the artist’s name—another Lohengrin!—based on the extensive evidence gathered by the curators and previous scholars. For this reason, I refer to “him” rather than Van Asperen’s open-ended “they,” although we can better honor her admonition first to focus on the works, and only after to raise questions, and to consider possible answers.

Let us start by acknowledging the elephant in the room, a phrase from a Russian story about an actual elephant in a museum, now used to refer to an uncomfortable yet conspicuous fact. Man with a Growth on his Nose from 1645 in Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum could have been a catalogue cover or poster image, yet the curators likely did not want to sensationalize the artist’s pre-occupation with physical deformities. Van Asperen judiciously characterizes his “empathic approach.” Yet Master I. S. is less like a sensitive doctor or medical student than a sensitive mad scientist, his composition a physiognomic train-wreck, which as one of the most bizarre images in the history of art already earns him a place in the canon. The man’s opulent fur coat and medallion on a gold chain around his neck with a crowned figure evoke an advisor to a king, like Polonius, a Northern counterpart of Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a medallion of Alexander the Great. The otherwise distinguished gentleman does not moderate or normalize the abnormal, but rather strengthens the shock, and our gawk, at his most unfortunate nose. As in the case of the actual “elephant man,” underscored by the pop star Michael Jackson’s obsession with him, the predicament reminds us that we all potentially have imperfect skeletons in our closets.

We cannot be certain if this man was an actual person or simply a fictive character, and the painter could have easily adapted in some way the growth on the nose, among other elements of his appearance. That is the case with any portrait. Yet Master I. S. deliberately brought such ambiguities or masterful mysteries to the fore.

The same uncertainties apply to the woman with a large wart on her left upper eye lid a man with his presumably blind left eye sewn shut, and a woman with a partially deformed (or seemingly shrunken) jaw—to characterize the most extreme examples in terms of what they actually depict.

Master I.S., Portrait of a Woman, Facing Left with a Wart on her upper left Eyelid, ca. 1650 private collection. courtesy of Nicholas Hall

Portrait of anOld Woman from 1651 in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches museum, chosen for the catalogue cover and exhibition poster, is more subtle. She stares straight ahead, her lips pressed around a perhaps toothless mouth, her skin criss-crossed by innumerable wrinkles and imperfections, with irritations or a rash on her right eye-lids and lower left jowl, which cannot be called afflictions, yet might have been left out of a formal portrait. Along with her coat with fine brown fur collar and elegantly folded neck scarf, the convincing cubic structure of her head is set off by a semi-transparent wrinkled veil of multicolored earth tones, wrapped in the manner of a turban around her forehead and a patterned head covering beneath, culminating in conventional stripes and fringe. Scholars have long associated the master’s costumes with northern and north-eastern Europe (the Baltic region), underscored by examples elucidated in the catalogue essay by the costume expert Marieke de Winkel and the Rembrandt school scholar Volker Manuth, who in a brilliant piece of visual sleuthing identified the repeated motif of a daisy chain on hems as a pictorial signature. As their essay observes, physical infirmities, and attitudes that seem to reflect hard work or difficult lives, are at odds with costly and exotic clothing.

The true mystery of Master I. S. resides in his singular vision as an artist, rather than his biography, although these dimensions are inextricable. The exhibition’s evocative title, “Masterful Mystery,” perhaps inverts the emphasis of the mysterious mastery of this fascinating, under-rated artist. Théophile Thoré’s “discovery” a century and a half ago of the unrecognized genius Johannes Vermeer, for which Thoré coined the phrase “the riddle of the sphinx of Delft,” offers a parallel. Scholars have contested his notion insofar as Vermeer’s paintings were appreciated by his contemporaries. That was presumably also the case, to a lesser extent, for Master I. S. Yet both artists were, in the hackneyed phrase, “ahead of their time,” or more important than contemporary viewers or writers on art could possibly have recognized or articulated. These painters are merely extreme cases of this rule of the history of art and the tasks of the modern discipline of art history, to discover facts about artists, to gather and to order their works, and to explain the significance of their art.

A core of the mystery of Master I. S. connecting his art and his biography involves the assumption that he studied in Leiden, perhaps coming from elsewhere, and combining an avocation as painter with a primary vocation such as doctor or lawyer. The assumption is based partly on his depictions of scholars in study rooms, including possible self-portraits, and partly on connections between his paintings and those of young Rembrandt, his rival Jan Lievens, and Rembrandt’s first student Gerrit Dou, often called the founder of the “Leiden school” of “fine painting”

The exhibition offers concrete visual evidence in a wide range of etched and painted study heads, called tronies [heads], which pose profound questions about the Leiden school, not only in relation to Master I. S. The catalogue adopts the conventional definition of tronie as the head of an anonymous model, which is already contradicted by Rembrandt and Lievens’ self-portrait studies. Earlier commentators identified their images of the same old woman as based on Rembrandt’s mother, which more recent scholars including in the catalogue reject as lacking evidence. Aside from precedents such as Albrecht Dürer’s images of his mother, the mayor of Leiden Jan Orlers’ Description of Leiden from 1642 reported in the first biography of Lievens that he gained renown for painting his mother in 1621, when he was only fourteen. Most importantly, we have the visual evidence of the works themselves, the reason for our explanations.

Lievens’ huge painting from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum of a rather brutal-looking woman holding a large open volume is dated on the wall label 1625-1626 and in the catalogue 1626-1633, which since he left Leiden in 1631 seems an unusually broad range, yet perhaps not broad enough. As evident from her relief-like head and torso, the stripes of her headcloth spread along the picture surface, the repeated rounded folds of her monotone light purple jacket, the crude brushstrokes indicating highlights on her face, and the inorganic relation between the book and her body, notably hands that seem to belong to different persons, a characteristic difficulty of Lievens, this composition was plausibly among his earliest. The painting was likely the 1621 portrait of his mother, as a prophetess, admittedly (made to look) surprisingly haggard for her forty-one years, although she died the following year. The composition also exemplifies, perhaps more than any other, what Constantijn Huygens later described as Lievens’ “grandeur” and “inventiveness,” including his invention of a new genre of the portrait-tronie. As evident from other works in the show, Lievens continued to refine his observations and techniques, yet did not develop the portrait-tronie further and never surpassed this earliest masterpiece or his fame as a precocious teen, and instead rested lazily on his laurels, cast in what Rudi Ekkart called “Rembrandt’s shadow.” Conversely,

Dou’s painting from ca. 1631, also from the Rijksmuseum, portrays a different older woman in profile, with a pointed nose, high forehead, and prominent cheekbones, who holds a bible open to the Gospel of St. Luke, and gazes at the picture, most likely based on Rembrandt’s (illiterate) sixty-three-year-old mother, as earlier commentators assumed. Dou excelled at tronies, creating what is now widely beloved as a Dutch national treasure, and perhaps his most original work.

Rembrandt’s small study from Salzburg from ca. 1630 included in the show, of the same yet obviously decrepit old woman (his mother) with hands clasped in prayer, even on its tiny scale, is far more accomplished in representing three-dimensional volume, detail, and psychology.

Yet the appropriate counterpart, his Prophetess Hannah which the Rijksmuseum was perhaps reluctant to lend, outstripped both Lievens and Dou at their own respective strengths. His mysterious evocation of a prophetess who, as Svetlana Alpers observed long ago, appears to feel the pseudo-Hebrew script as if braille, can reasonably be called “the mother of all mother portrait-tronies.” Rembrandt’s family members also served as models for many other paintings by Lievens and Dou, some of which are still mistakenly attributed to Rembrandt. Several times Rembrandt paired his mother with his bald and bearded father as models, he repeatedly portrayed his eldest brother Gerrit, who damaged his hand in the family mill and stayed at home where he was accessible as model (called “Rembrandt’s father” by early commentators because Dou paired him with Rembrandt’s mother as model), and also his youngest sister Lijsbeth, who was mentally disabled. Rembrandt already depicted himself, his mother, brother, and sister as models for historical characters as the Prodigal Son in the Tavern in his so-called “Family Concert” currently in the Lakenhal, yet outside the exhibition. By such means, he eventually re-invented the tronie, the self-portrait, and history painting.

How does Master I. S. stack up against these masterpieces? His Portrait of an Old Woman, the title of which already indicates more than an anonymous figure, conveys as much grandeur in its understated way as any work by Lievens, equals Dou in detailed finesse, and vies with Rembrandt in psychological profundity. Why shouldn’t we say it, for whom could we offend? In certain respects, Master I. S. surpasses Lievens and Dou and comes as close as one can to Rembrandt. In its perspicacious ugliness, the composition is even a counterpart of, and as compelling as, the idealized beauty of Girl with a Pearl Earring, now the most famous tronie in the world. A Kunstschrift essay claimed that scientific testing has proved Vermeer’s tronie to be an anonymous individual, yet we can always use our eyes and minds to judge for ourselves. Did Andrew Graham-Dixon finally “crack the code” in his recent biography, as one journalist asked, in identifying the girl as the daughter of Vermeer’s patron? Or was she based on his own eldest daughter Maria as model, as repeatedly proposed by scholars going back to the beginning of the previous century? As noted in another Kunstschrift essay, she herself possibly painted “some tronies of young girls,” along with several other contested compositions assigned to her father that do not correspond to his approach.

Master I. S.’s works thus connect to broader unresolved mysteries of Dutch, or Netherlandish painting. Scholars claim that tronies originated in Italy and Flanders in Rubens’ workshop and his predecessors, yet roots can always be traced further back. Jan van Eyck made portraits of himself, his wife, and friends, which come closer in their intimate approach to portrait-tronies than to formal social portraits. He thereby laid the foundations of a tradition that Master I. S. made his own, presumably first in Leiden, and elaborated on and contributed to in his “mature” works over decades, extending the geographical and conceptual boundaries of Northern art. His tradition also implicitly encompassed the likes of the Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, who declared that “there is nothing more cinematic than the human face.” In all these examples, the model or sitter for a tronie in relation to the artist is potentially profoundly important. On the other hand, what Oscar Wilde declared in Portrait of Dorian Gray, that “a picture painted with feeling is more a portrait of the artist than the sitter,” is even more the case for a tronie. Even if we do not know the names of his sitters or models, or Master I. S. himself, through his extraordinary mastery and original conceptions, we can nevertheless learn to know them, or in Nietzsche’s phrase, learn to love them.

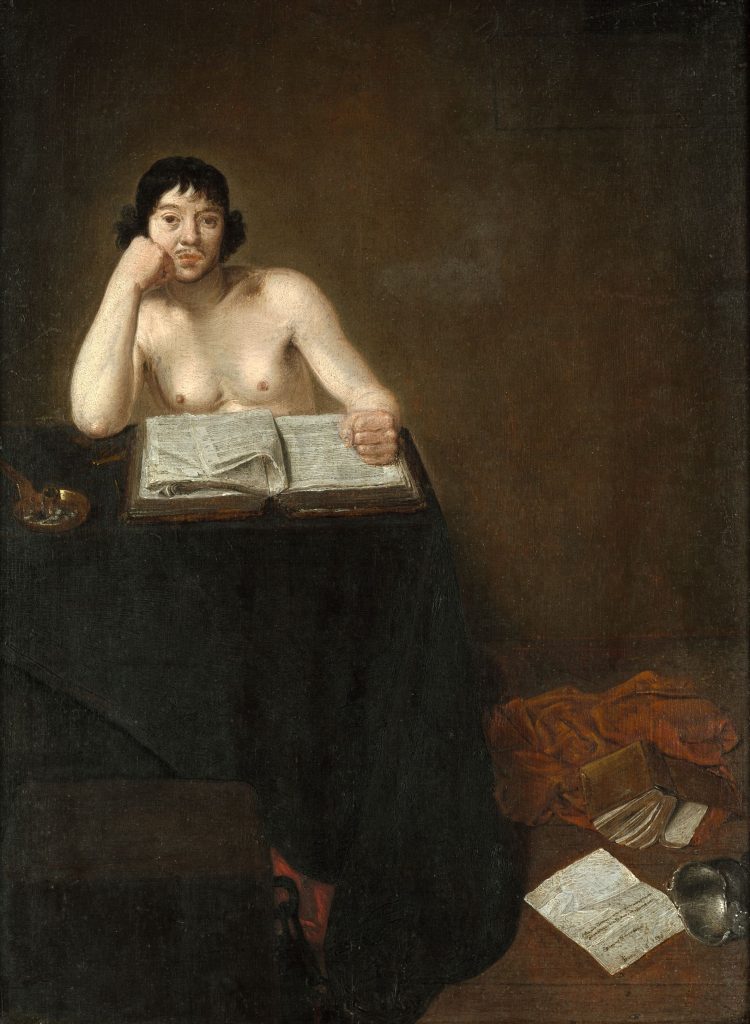

Master I.S. Young Scholar half Naked (selfportrait?), 1631, private collection, courtesy of David Bassenge

A last must-see painting in the exhibition is a presumed self-portrait as a half-naked student in a study room from 1634. Leaning on his right fist in the traditional melancholy pose, the figure clenches his left fist on a large open volume with papers curiously crumpled on the wrong (left) side, alongside a candle holder with burned-down candle, suggesting a choleric element or frustration with study. Clothing, an upside-down book, a letter, and an over-turned silver (piss?) pot lie scattered on the floor to the right. Behind a large block with a chain in the foreground we glimpse what look like flames of hell beneath the tablecloth, possibly meant to be associated with the figure’s genitals below the table, behind which he could be fully naked. A dissatisfied student, turning to self-portraiture as an alternative form of self-expression, corresponds exactly to assumptions about Master I. S.’s career. The scene also calls to mind Faust in his study room before conjuring Mephistopheles, and the figure is undeniably Mephistophelean. The curator Van Asperen adopted the pronoun “they,” not simply because Master I. S.’s identity is unknown, but also in relation to the figure’s ambiguously gendered hair and what resemble breasts, which Boris de Munnick at the exhibition characterized as “gender fluidity,” although Judith Butler’s coinage “gender trouble” is more pertinent. Daunting intellectual tasks related to troubled sexuality and gender were in keeping with traditional notions of melancholy associated with artists, as evident from Dürer’s Melancholia engraving, and an essay by the late J. Salomonson proposed that the painting was one of several self-portraits by Master I. S. embodying different temperaments.

Master I.S. Portrait of a Young Man with with a Tall Fur Hat and Gorget self-portrait, 1638 private collection courtesy of Johnny van Haeften

A final self-portrait tronie from 1638 illustrated in the catalogue, which was not included in the exhibition, shows the artist with shoulder-length frizzy curly hair that recalls young Rembrandt, in a metal gorget of the type he and Lievens wore in their self-portrait-tronies. Master I. S. wears the gorget with a medallion on a gold chain, over a cloak with an elaborately embroidered pattern and frogging down the front, a clumsily-rendered brownish fringed shawl around his shoulders, and a tall fur hat with a V-shaped opening at the front, with an elaborately set jewel with a pearl.

Rembrandt’s 1630 tronie from Innsbruck included in the exhibition, developed the head rabbi in his Judas Returning the Thirty Silver Pieces of the previous year based on the same model in the same hat, identified by the Rembrandt Research Project and others as an eastern European Jewish kolpak (or shtremiel). Was I. S. competing with Rembrandt, substituting an eastern European Christian tall fur hat?

Tomi Moisio pointed in his catalogue essay to the similar features and costume in a portrait from the 1640’s in Warsaw of John II Casimir Vasa, King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania, and first son of the Swedish King, by the German-speaking Polish-Lithuanian court painter Daniel Schultz, whose other portraits of John II Casimir, as Moisio observed, are entirely different, specifically, not as naturalistic. Daniel Schultz appears to have portrayed the Polish King along the lines of the unknown Master I. S.’s earlier self-portrait-tronie, emulating his superior technique and conception, and possibly thereby gaining his position as court painter. What connected them? Daniel Schultz, who signed his works D. S., might today be called the Master D. S., had the documents recording his name been lost, as with so many in those “bloodlands” under the Swedes, long before the Nazis, let alone the Russians. His family of painters included an uncle of the same name, and Johannes Schultz in Munich the following century, whose short dark hair and thin moustache resemble those of Master I. S. Could the latter have been another eponymous member of this family of German-speaking artists, and a Lutheran, as posited in the catalogue in relation to his series of small portraits, likely painted as a favour, for a family of German Lutherans? This solution to the enigma was inadvertently leaked and mistakenly attributed to the catalogue in a prior review, but not the final piece of the puzzle. As it turns out, a Johannes Schultz from Lutheran Wittenberg, perhaps his place of origin or a prior university stint, enrolled at age twenty in Leiden University’s Law faculty in 1634, the year of the self-portrait as a half-naked student by Master I. S., possibly Johannes Schultz (most previous attempts to identify the initials aassumed “I.” referred to a “J.” name, specifically Johannes).[1] Regardless of his name, the mysterious art of the Master I. S., brilliantly presented in the Lakenhal exhibition, offers a unique opportunity to see, and think through, images.

[1] Album studiosorum Academiae Lugduno Batavae MDLXXV-MDCCCLXXV, pp. 265, 338, 395, https://books.google.nl/books?id=vxa7siqSndcC&printsec=frontcover&hl=nl&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=schultz&f=false. This Johannes Schultz was born in 1614, whereas Daniel Schultz, who studied Law in Leiden at twenty-seven in 1642, born in 1615, could have been his younger brother by one year or a cousin. Another Johannes Schultz from Riga, who enrolled in the Law faculty at twenty-six in 1649, born in 1623, was possibly a cousin of the first Johannes Schultz.

Benjamin Binstock taught art history at colleges in New York City before moving with his family to Amsterdam in 2018. His Vermeer’s Family Secrets: Genius, Discovery, and the Unknown Apprentice from 2008 offered the first painting-by-painting account of Johannes Vermeer’s development and re-assigned one-fifth of those now attributed to him to his eldest daughter Maria as his secret apprentice. The book was hailed as “the most comprehensive and detailed analysis ever published of Vermeer… full of ideas that could fundamentally change the current understanding of his paintings,” the subject of an all-day symposium in 2013, and recently revisited in an essay The Atlantic in 2023.

Extra information: